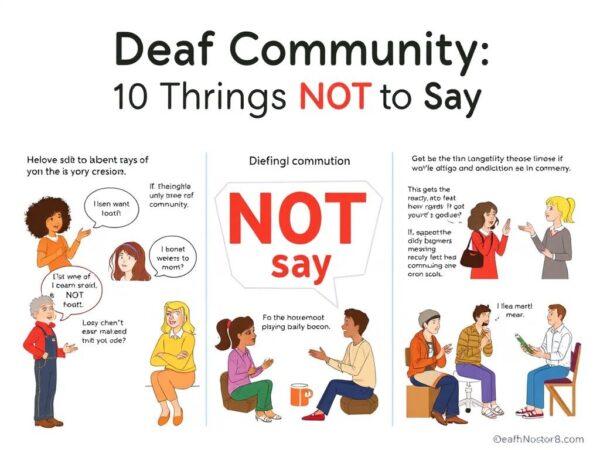

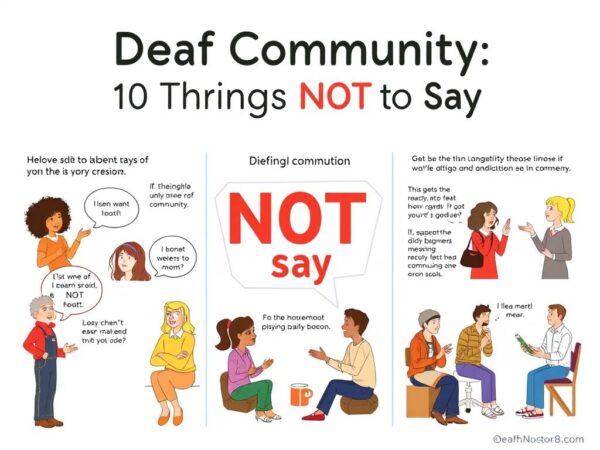

Deaf Community, While most hearing individuals strive to be polite, certain common phrases, often uttered without malice, can inadvertently create barriers, cause offense, or perpetuate harmful stereotypes. As Dr. Elena Petrova, a leading expert in intercultural communication and disability studies, emphasizes, “Effective communication bridges worlds, but careless language can inadvertently build walls.

“Is there a sign for that?”

The question “Is there a sign for that?” often arises when a hearing person encounters American Sign Language (ASL) for the first time, or when they observe a deaf person signing. While it might seem like an innocent query born of curiosity, it can be problematic for several reasons. Firstly, it oversimplifies the complexity and richness of ASL, treating it as a mere collection of individual signs for English words, rather than a distinct language with its own grammar, syntax, and cultural nuances. ASL is not a signed version of English; it is a complete and natural language. Secondly, it often places an immediate burden on the deaf individual to become a language instructor on the spot, disrupting the flow of conversation and potentially making them feel like a spectacle. For Leo, a lifelong ASL user, it’s a common, tiresome interaction: “I’m just trying to have a conversation, and suddenly I’m expected to teach a mini-lesson. It makes me feel like my language is a novelty, not a valid form of communication.” Instead of making such a direct demand, a more respectful approach would be to express genuine interest in ASL, perhaps by saying, “I’m fascinated by ASL; I’d love to learn more sometime,” or even better, take the initiative to learn some basic signs yourself.

“Can you hear me now?”

The repeated or excessively loud question “Can you hear me now?” is a common communication blunder that can be deeply frustrating for deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. This phrase often stems from a hearing person’s discomfort or impatience when their initial spoken words are not immediately understood, leading them to assume that simply increasing volume will solve the problem. However, for many deaf individuals, particularly those with profound hearing loss, simply speaking louder does not improve comprehension; it can distort sounds, cause discomfort, or even pain. It also places the onus entirely on the deaf person to “hear better,” rather than on the hearing person to adjust their communication method. Professor Robert Gallaudet, a communication access advocate, notes, “Shouting ‘Can you hear me now?’ is often counterproductive. It implies a lack of understanding of hearing loss, which is not just about volume, but about clarity, frequency, and speech discrimination.” Imagine someone continually shouting at you when you’ve already indicated you can’t understand them. For Sarah, who uses hearing aids, it’s a daily annoyance: “When people shout, it just makes everything garbled and painful. It doesn’t help me understand; it just makes me want to disengage.” Instead of repeating the same phrase louder, try rephrasing your sentence, speaking clearly at a normal pace (unless requested otherwise), or using alternative communication methods like writing, typing on a phone, or using visual cues.

“You’re so brave/inspirational!”

While seemingly complimentary, the phrases “You’re so brave!” or “You’re such an inspiration!” when directed at a deaf person for simply navigating everyday life, can be deeply uncomfortable, patronizing, and even offensive. These comments often stem from a hearing person’s limited understanding of disability, viewing the deaf individual’s existence through a lens of struggle and overcoming, rather than as a normal, lived experience. It implies that performing routine tasks like going to work, raising a family, or engaging in hobbies is inherently extraordinary or courageous simply because one is deaf. This perspective inadvertently diminishes the individual’s autonomy and reduces them to their disability, rather than acknowledging their inherent capabilities and resilience. We are here to live our lives.” Imagine being lauded as “brave” for grocery shopping or doing laundry. For Kenji, a deaf software engineer, it’s a frequent, irritating encounter: “I’m just living my life, like anyone else. When someone calls me ‘inspirational’ for going to the store, it feels like they think my life must be so hard, which it isn’t, in the way they imagine.” Instead of offering unsolicited praise for mundane activities, treat deaf individuals as competent, ordinary people. Acknowledge their achievements and contributions in the same way you would anyone else’s, focusing on their skills, talents, and character, rather than their deafness.

“It must be so quiet!” / “Do you hear anything at all?”

The intrusive questions “It must be so quiet!” or “Do you hear anything at all?” are common inquiries that, while perhaps driven by curiosity, are often deeply personal and can be insensitive to deaf individuals. These questions typically stem from a hearing person’s attempt to imagine the deaf experience through their own auditory framework, failing to recognize the vast spectrum of hearing loss and the diverse ways deaf people perceive and interact with sound (or its absence). For many, the concept of “quiet” is irrelevant, as they may have never experienced sound, or they may experience sound differently (e.g., muffled, distorted, or as vibrations). Furthermore, these questions can feel like an invasion of privacy, demanding personal medical information or an explanation of a deeply subjective experience. Professor John Smith, an expert in audiology and deaf culture, emphasizes, “These questions reduce a complex sensory experience to a simplistic binary. They also impose a hearing-centric view of the world, assuming that the absence of sound is inherently negative or fascinating in a voyeuristic way.” Imagine someone asking you about the exact nature of your vision or taste. For Lisa, who has progressive hearing loss, it’s a constant reminder of her difference: “I don’t know what ‘quiet’ means to them. And no, I don’t ‘hear’ anything in the way they do. It’s an uncomfortable question.” Instead of asking about their auditory perception, focus on communication and connection. If you are genuinely interested in their lived experience, you might explore resources on Deaf culture or personal narratives shared by deaf individuals, respecting their right to privacy in direct conversation.

“I’m sorry” (when learning someone is deaf)

The immediate reaction “I’m sorry” upon learning that someone is deaf is a common, yet often unwelcome, response that inadvertently frames deafness as a tragedy, a misfortune, or something to be pitied. This phrase, while well-intentioned, reflects a medical model of disability that views deafness as a deficit that evokes sympathy, rather than acknowledging it as a neutral characteristic, a lived experience, or even a source of cultural identity and pride for many within the Deaf community. It implies that the deaf person’s life is inherently diminished or that they are suffering. This reaction can be particularly frustrating for individuals who are content with their deafness and do not perceive it as something to be apologized for. Dr. Christine Sun Kim, a celebrated Deaf artist and activist, often speaks about the absurdity of this reaction, highlighting that deafness is simply a way of being. Imagine someone apologizing to you because you have brown hair or are left-handed. For Daniel, who grew up within the Deaf community, it’s a constant source of mild irritation: “When people say ‘I’m sorry,’ it feels like they’re mourning something that isn’t lost. I’m not sad about being deaf; it’s just who I am.”

“I’ll just tell your friend/family member.”

The dismissive phrase “I’ll just tell your friend/family member” is one of the most disempowering and frustrating comments a deaf individual can encounter, as it completely bypasses them in a conversation or interaction. This statement implies that the deaf person is incapable of understanding or participating directly, effectively rendering them invisible or irrelevant in their own presence. It strips them of their autonomy and agency, forcing them to rely on a third party for information that is directly addressed to them. This often happens in public settings, at service counters, or in group conversations, where hearing individuals might perceive it as “easier” or “quicker” to speak to an accompanying hearing person. Such experiences are deeply alienating and can lead to feelings of frustration, anger, and profound exclusion. Dr. Robert Johnson, a disability rights advocate, emphasizes, “Bypassing a deaf person to speak to their companion is a direct violation of their right to direct communication and participation. It’s a blatant act of audism that denies their presence and capability.” Imagine being in a room and having someone talk about you, to someone else, as if you weren’t there. For Aisha, who uses a sign language interpreter, this is a frequent and infuriating occurrence: “My interpreter is for me, not for you to talk to. When you speak to my friend instead, you’re telling me I don’t matter.” Instead of resorting to this dismissive tactic, always direct your communication to the deaf individual themselves. If an interpreter is present, speak directly to the deaf person, maintaining eye contact with them, not the interpreter. If there’s no interpreter, offer to write, type, or find another way to communicate directly. Prioritizing their direct involvement and respecting their right to communicate for themselves is fundamental to inclusive interaction.

“Is there a cure for that?”

The question “Is there a cure for that?” when directed at a deaf person, is deeply problematic and reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of deafness, often perceived as an insult rather than genuine curiosity. This phrase immediately frames deafness as a disease or an affliction that needs to be “fixed,” rather than acknowledging it as a human variation or, for many, a core aspect of their identity and culture. It disregards the vibrant Deaf culture, which cherishes American Sign Language (ASL) and views deafness as a shared experience, not a medical deficiency. For many deaf individuals, particularly those born into Deaf families or who embrace Deaf culture, there is no desire for a “cure” for something they do not consider an illness. Dr. Ben Carter, a Deaf scholar and advocate, states, “Asking about a cure implies that our existence is inherently flawed, that we are broken and need repair. It completely overlooks the richness of our language, our community, and our way of life.” Consider the personal experience of Maria, who was born deaf: “When people ask about a cure, it’s like they’re telling me my life isn’t complete or good enough as it is. My deafness is part of who I am, not something to be eradicated.” This question also ignores the reality that even with hearing aids or cochlear implants, perfect hearing is rarely, if ever, achieved. Instead of focusing on a “cure,” a more respectful approach is to ask, “How do you prefer to communicate?” or “What communication methods work best for you?” This shifts the focus from perceived deficit to practical communication, demonstrating respect for their identity and autonomy.

“You speak so well for a deaf person!”

The seemingly complimentary phrase “You speak so well for a deaf person!” is, in reality, a backhanded compliment that carries a heavy burden of unintended bias and can be deeply offensive. This comment reveals an underlying assumption that deaf individuals are inherently incapable of clear verbal communication, thereby expressing surprise when they defy this stereotype. It inadvertently prioritizes spoken language over other valid forms of communication, such as sign language, and diminishes the significant effort many deaf individuals put into developing their speech. This phrase can feel condescending, reducing a person’s entire identity and communication abilities to a single, often hard-won, skill. Professor Laura Kim, a sociolinguist specializing in language and disability, explains, “This remark is rooted in audism, the belief that hearing and speaking are superior. It’s not a compliment; it’s an expression of surprise that a deaf person deviates from a prejudiced expectation, implying their ‘normal’ state is to be less capable.” Imagine being praised for simply walking or breathing. For Alex, who uses both ASL and spoken English, the comment is a constant reminder of societal judgment: “It makes me feel like I’m being graded on my ‘hearing’ performance, not on what I’m actually saying. It’s exhausting to constantly prove that I’m competent.” Instead of focusing on how they speak, focus on what they are saying. Engage with the content of their message, treat them as capable communicators, and respect their chosen method of expression, whether it involves voice, sign language, or other aids. The goal is genuine understanding, not a surprised assessment of their vocal abilities.

“My friend’s cousin’s neighbor is deaf too!”

The statement “My friend’s cousin’s neighbor is deaf too!” often comes from a well-intentioned place, aiming to find common ground or show empathy, but it frequently falls flat and can be perceived as trivializing or tokenizing. This phrase, while attempting to relate, often reduces a deaf individual’s complex identity and experiences to a singular characteristic. It implies that knowing one deaf person means understanding all deaf people, ignoring the vast diversity within the deaf community in terms of communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, life experiences, and degrees of hearing loss. It can also feel like an attempt to establish a connection based on a shared “otherness” rather than genuine interest in the individual. Dr. David Miller, a sociologist studying identity and community, notes, “This comment, though benign in intent, can inadvertently flatten a rich identity into a mere label. It suggests a superficial understanding of diversity, where one representative is enough to ‘know’ an entire group.” Consider the personal experience of Sam, a deaf artist: “When someone says that, I just nod. It’s like they think we’re all the same, or that my deafness is the most interesting thing about me. I’d rather they just ask about my art.” Instead of trying to find a distant, tenuous connection through their disability, focus on getting to know the individual in front of you. Ask about their interests, hobbies, profession, or anything else that would be part of a normal conversation. Treat them as an individual with unique experiences, rather than as a representative of a broad category. Genuine connection comes from curiosity about them, not about their connection to someone else’s distant acquaintance.

“Is it hard to drive?”

The question “Is it hard to drive?” or similar inquiries about daily activities like cooking, shopping, or working, often stems from a misconception that deafness inherently limits a person’s ability to perform routine tasks. This question implies a lack of understanding about how deaf individuals navigate the world successfully and independently, often relying on visual cues, adaptive strategies, and technological aids. It can be frustrating because it suggests a fundamental incapacity where none exists, overlooking the fact that many deaf individuals are highly skilled drivers, professionals, and active participants in society. The ability to drive, for instance, is primarily a visual task, and deaf individuals are often highly attuned to visual information. Professor Jane Liu, an expert in disability and independent living, states, “These questions reveal a deficit model of thinking, where deafness is seen as a barrier to all aspects of life, rather than a characteristic that simply requires different approaches or adaptations. It’s an outdated perspective.” Imagine being asked if it’s hard for you to read a book because you wear glasses. For Carlos, a deaf truck driver, this question is particularly irksome: “I’ve been driving for 20 years. My eyes are on the road, not my ears. It’s frustrating to constantly explain that my deafness doesn’t make me a worse driver.” Instead of questioning their capabilities, assume competence.

Here are 10 FAQs based on the content provided for “Deaf Community: 10 Things NOT to Say!”:

1. Why is it important for hearing people to be aware of what not to say to deaf individuals?

It’s crucial for fostering respectful and effective communication, building genuine connections, and creating truly inclusive environments. Certain common phrases, though often well-intentioned, can inadvertently cause frustration, discomfort, or offense, perpetuating stereotypes and leading to feelings of exclusion for deaf individuals.

2. Why is asking “Can you read lips?” problematic?

Lip-reading is an incredibly difficult and often inaccurate skill, with only a small percentage of speech sounds being visually distinguishable. Asking this question places an unfair burden on the deaf person and assumes it’s a universal solution, rather than acknowledging the complexity of visual communication.

3. What’s wrong with saying “Oh, you can talk!” to a deaf person?

This exclamation, while seemingly complimentary, implies surprise and preconceived notions that deafness inherently means an inability to speak. It can feel like a backhanded compliment, reducing the deaf individual to their vocal ability and disregarding the validity of Deaf culture and sign language.

4. Why should I avoid saying “Never mind, I’ll tell you later”?

This phrase is dismissive and isolating. It implies that the deaf person’s participation or understanding isn’t worth the effort, effectively excluding them from the conversation and leading to feelings of being unimportant or invisible.

5. Is it offensive to ask “Why don’t you just get hearing aids?” or “Why don’t you get a cochlear implant?”

Yes, it can be offensive. These questions fundamentally misunderstand that hearing aids or implants are not a “cure” and do not restore normal hearing. They are personal choices, and the questions can feel intrusive, judgmental, and dismissive of Deaf culture and identity.

6. Why is “Is there a sign for that?” considered problematic?

This question oversimplifies American Sign Language (ASL), treating it as a direct translation of English words rather than a distinct language with its own grammar. It also often places an immediate, unwelcome burden on the deaf person to provide an impromptu language lesson.

7. Why shouldn’t I repeatedly ask “Can you hear me now?” or just speak louder?

For many deaf individuals, simply increasing volume does not improve comprehension and can even distort sounds or cause discomfort. It places the onus on the deaf person to “hear better” rather than on the hearing person to adapt their communication strategy.

8. Why is calling a deaf person “brave” or “inspirational” for everyday activities inappropriate?

These comments, while seemingly positive, can be patronizing and uncomfortable. They imply that performing routine tasks is extraordinary simply because one is deaf, reducing the individual to their disability and overlooking their inherent capabilities and resilience.

9. Why are questions like “It must be so quiet!” or “Do you hear anything at all?” insensitive?

These questions are often intrusive and reflect a hearing-centric view of the world. They demand personal information about a subjective sensory experience and can be insensitive to the vast spectrum of hearing loss and how deaf individuals perceive sound (or its absence).

10. What’s wrong with saying “I’m sorry” when you learn someone is deaf?

Saying “I’m sorry” frames deafness as a tragedy or something to be pitied. It reflects a medical model of disability and can be frustrating for individuals who are content with their deafness and do not view it as something to be apologized for, but rather a part of their identity.